How to communicate with patients more effective

Today early drop-out still is a major challenge we must deal with when running clinical trials. The past few years patient centricity and patient engagement initiatives have generated major improvements. This is the second in a series of articles about a different perspective on the subject and a new and innovative approach to improve early drop-out rates.

Communicating information effectively

In our previous article we have established that the key reasons for early drop-out have to do with misconceptions and wrong expectations. And that when we communicate information with patients, we clearly are not hitting the target.

If we want to understand how we can make communication with patients more effective, we first need to understand what information is and what it can do.

Information is data that is (1) accurate and timely, (2) specific and organized for a purpose, (3) presented within a context that gives it meaning and relevance, and (4) can lead to an increase in understanding and decrease in uncertainty. This is exactly what the Informed Consent process is all about.

Information is valuable because it can affect behavior, a decision, or an outcome. In other words; if we don’t meet all four criteria data does not transform into information and therefore has no value.

All of us form an expectation of things to come based on the data we gather and receive. If that data turns out not meet the above criteria for information, then we risk making the wrong decisions and ultimately being disappointed about the outcome.

We also need to consider the way and form data is communicated. And communication is only effective if it:

- Leaves no questions in the mind of the audience

- Is concise

- Take the audience into consideration

- Is clear, specific and simple

- Shows respect for the audience

- Is repeated and confirmed by feedback

I believe we can all agree that the information we share during the Informed Consent process meets all the above requirements if we take trial participants as a group. However, each patient has his personal reasons to drop out and we should align the way we convey information to each patient individually.

In practice this is not feasible because of the workload of site personnel. During site visit there is simply not enough time to gauge every patient’s individual need and capability and align the information and support we should provide. But with very limited extra effort the Subjective Experienced Health Method (SEHM) can help reach this goal to a large extend.

SEHM based communication for Clinical Trials

The Subjective Experienced Health Method (SEHM) is originally developed at the Nyenrode Business University, The Netherlands by Prof Sjaak Bloem[1]. It enables healthcare providers to better align products and services to the actual needs of a patient at a specific point in time. It has been successfully put into practice and fine-tuned for oncology, hematology, infectious diseases, diabetes and pulmonary diseases.

At Link2Trials we use SEHM is to better align retention activities to the actual needs and wants of an individual patient. With SEHM early drop-out management takes a holistic approach focused on prevention instead of firefighting.

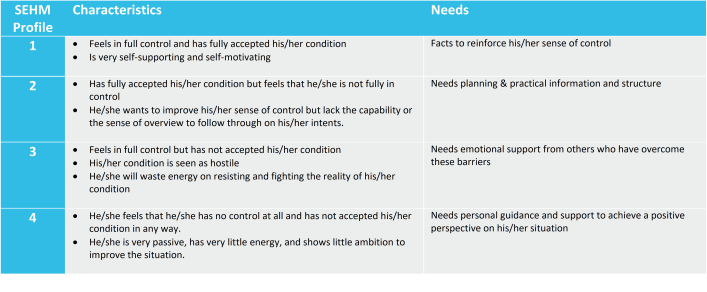

SEHM is based on three building blocks;

- a set of personality/mood types (SEHM profile),

- a simple questionnaire to quickly and regularly determine each patient’s present SEHM profile,

- a set of communication and interaction guidelines per SEHM profile.

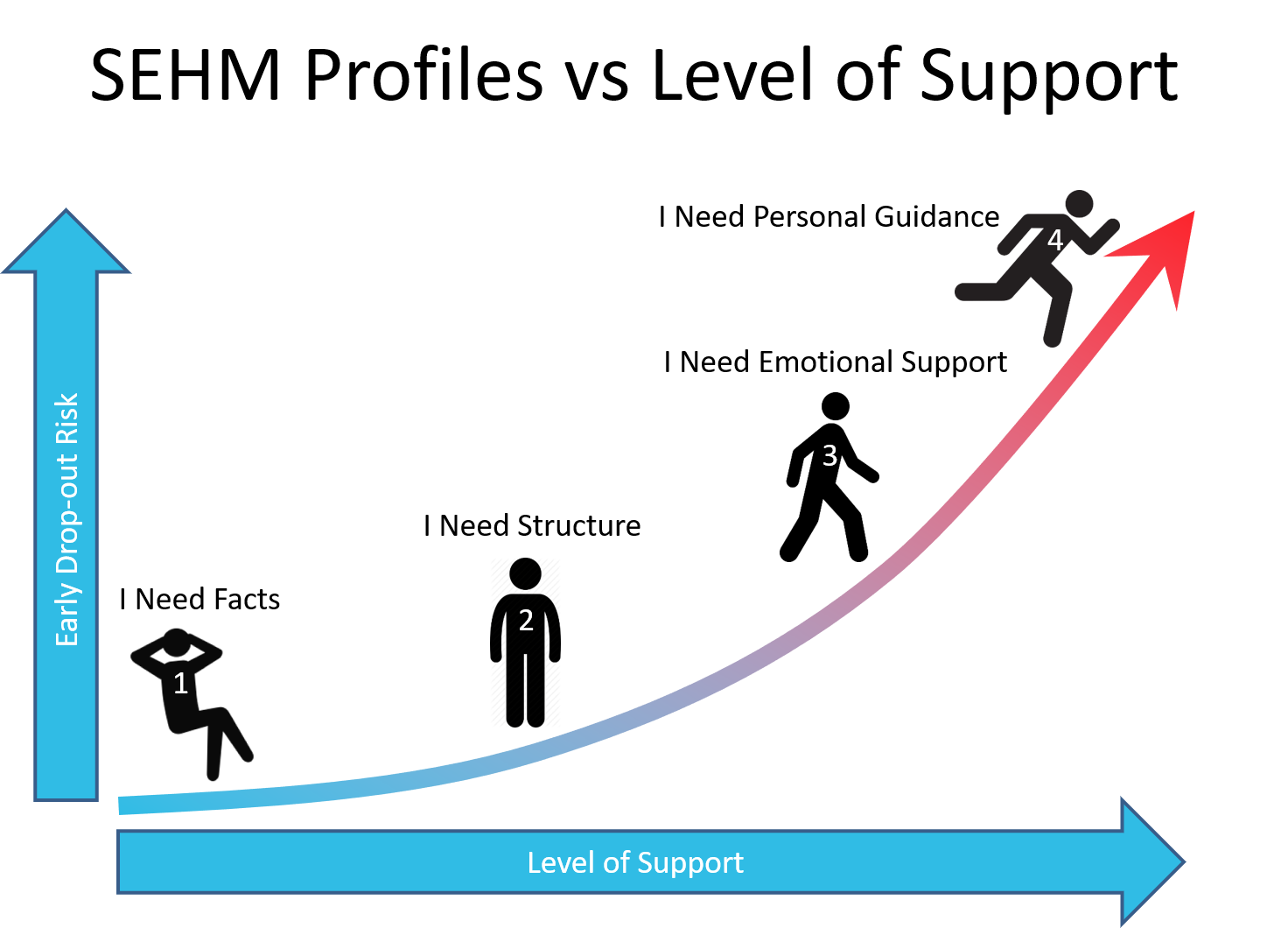

Everyone has experienced that your mood can swing from confident to insecure depending on the situation you are in. And we all know that if you feel insecure you are reluctant to stay in a risk full environment, i.e. you want to drop-out. The only way you can be persuaded to stay is when someone or something restores your confidence. SEHM will help you to focus on these individuals in your study population who are prone to drop-out soon.

SEHM is the most effective when it is integrated in the study from the very first beginning and all patients can be contacted directly. Through a simple questionnaire the baseline SEHM profile of each recruited patient is established, and during study execution it is checked regularly if this has shifted into another profile.

Based on the SEHM profile retention efforts and interactions can now be aligned to the needs of an individual patient. This could be pushing factual information about the study to a SEHM profile 1, sending out visit schedules and reminders to a SEHM profile 2, publishing testimonials from patients who have come to peace with the reality of their condition for a SEHM profile 3, or providing hand-holding and personal coaching to a SEHM profile 4.

Now how does this work out in practice? And what effects does it have on the day to day operations of a clinical trial?

Read our next article on the subject and learn how SEHM can be integrated in a study!

[1] Bloem, J.G. & Stalpers, J.F.G. (2012). Subjective experienced health as a driver of healthcare behaviour. Nyenrode research papers series no 12-01 (9 July). Nyenrode Business University, The Netherlands

Like or Share

Choose category

Latest posts

- 04 November, 2025

- Link2Trials Q&A_30

- 15 August, 2025

- Link2Trials Q&A_29

- 18 July, 2025

- Link2Trials Q&A_28

- 04 July, 2025

- Link2Trials Q&A_27

- 03 June, 2025

- Link2Trials Q&A_26

Argentina

Argentina Australia

Australia Balgarija

Balgarija België

België Canada

Canada Česko

Česko Chile

Chile China (中国)

China (中国) Colombia

Colombia Danmark

Danmark Deutschland

Deutschland England

England España

España France

France Ireland

Ireland Italiana

Italiana Lietuva

Lietuva Magyarország

Magyarország Nederland

Nederland New Zealand

New Zealand Österreich

Österreich Polska

Polska Schweiz

Schweiz Singapore

Singapore Slovenija

Slovenija Slovensko

Slovensko Suomi

Suomi Sverige

Sverige United States

United States Israel

Israel